|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:35:53 GMT

z3.invisionfree.com/The_Northern_Kingdom/index.php?showtopic=44AlcuinOrigins of the story of the fall of Arnor in the Text I was reading The Treason of Isengard this afternoon when in the chapter “The Council of Elrond (1)” I came across this passage in my paperback edition on pp 120-121 QUOTE (ii) ‘And the Men of Minas Tirith drove out my fathers,’ said Aragorn. ‘Is that not remembered, Boromir? The men of that town have never ceased to wage war on Sauron, but they have listened not seldom to counsels that came from him. In the days of Valandur they murmured against the Men of the West, and rose against them, and when they came back from battle with Sauron they refused them entry into the city. [footnote 13 here] The Valandur broke his sword on the city gates and went away north; and for long the heirs of Elendil dwelt at Osforod the Northburg in slowly waning glory and darkening days. But all the Northland has now long been waste; and all that are left of Elendil’s folk are few. ‘What do the men of Minas Tirith want with me – to return to aid [them] in the war and then reject me at the gates again?’ Following this is a discussion by Christopher Tolkien QUOTE The passage (ii) was struck through in pencil. … I think that this obscure story, with its notable suggestion of a subject population that was not Númenórean (although the cities were founded by Elendil), was rejected almost as soon as it was written; it may be that is was the earliest form of the history of the Númenórean realms in exile that my father conceived. Footnote 13 references this outline of the Council of Elrond on page 116, apparently written in August 1940 or soon after, which I read: QUOTE At Council. Aragorn’s ancestry Gloin’s quest – to ask after Bilbo. ? News of Balin. ?? Boromir. Prophecies had been spoken. The Broken Sword should be reforged. Our wise men said the Broken Sword was in Rivendell. I have the Broken Sword, said Tarkil. My fathers were driven out of your city when Sauron raised a rebellion, and he that is now the Chief of the Nine drove us out. Minas Morgul. War between Ond and the Wizard King. There Tarkil’s sires had been king. Tarkil will come and help Ond. Tarkil’s fathers had been driven out by the wizard that is now the Chief of the Nine. … I took several tidbits from this text. First, “Osforod the Northburg” is unmistakable as Fornost Erain, the Norbury of the Kings, and is later identified as such. (The predecessor of Annúminas appears in the next version of the telling.) “Valandur” has the same name as none other than the unfortunate eighth king of Arnor who was slain; his son Elendur was the last king of all Arnor. The phrase “in slowly waning glory and darkening days” is an apt description of the slow decay of Arnor and Arthedain. The statement that “The men of that town have never ceased to wage war on Sauron, but they have listened not seldom to counsels that came from him,” could well describe the condition of the Dúnedain of Arnor, who fought evil when it presented itself, but succumbed at least to some degree to the counsels of Morgul, either in the practice of Morgul or else in their own petty, internecine warfare. (Not that petty, internecine warfare cannot arise without the counsels of Morgul; but I think that evil influence is implied in the published history of Arnor as we know it.) “My fathers were driven out of your city when Sauron raised a rebellion, and he that is now the Chief of the Nine drove us out,” and “Tarkil’s fathers had been driven out by the wizard that is now the Chief of the Nine,” seem to me direct predecessors of the Witch-king’s conquest of Fornost Erain and the scattered flight of the royal house from the city. (Tarkil and Aragorn are two names for the same person; Tarkil is a Quenya word that was later replaceed with the Sindarin Dúnadan, but also the root of Snaga’s Orkish slur; Tolkien says in Appendix F that it was a “Quenya word used in Westron for one of Númenórean descent.”) “War between Ond and the Wizard King” was in fact the situation for Gondor (Ond), but it was also the situation for Arnor until its collapse and destruction. Finally, there is the interesting observation by Christopher Tolkien that there was “a subject population that was not Númenórean (although the cities were founded by Elendil)” that struck me as precisely what is being role-played here. I am reminded not only of “the hardy mountaineers of Ered Nimrais” in Gondor (Faramir’s description of the non-Númenórean native population recruited to strengthen Gondor’s armies and dwindling Númenórean bloodline by the Stewards in “Window on the West” in Two Towers) but also of the second paragraph of Fellowship of the Ring’s “At the Sign of the Prancing Pony”: QUOTE The Men of Bree were brown-haired, broad, and rather short, cheerful and independent: they belonged to nobody but themselves; but they were more friendly and familiar with Hobbits, Dwarves, Elves, and other inhabitants of the world about them than was (or is) usual with Big People. According to their own tales they were the original inhabitants and were the descendants of the first Men that ever wandered into the West of the middle-world. Few had survived the turmoils of the Elder Days; but when the Kings returned again over the Great Sea they had found the Bree-men still there, and they were still there now, when the memory of the old Kings had faded into the grass. I am not arguing for one-to-one correspondence in any of this material, but I think it is suggestive all the same. Arnor and Arthedain were “in slowly waning glory and darkening days.” Valandur was the eighth king of Arnor (properly the sixth: both Isildur and Elendil his father had been “High King” of both Arnor, which they ruled directly, and Gondor, ruled indirectly through a subject king), and as far as I know, the name was not reused anywhere else. It is not clear in the completed text why Valandur died, but if the non-Númenórean inhabitants in some part of the realm, or just outside it (I am thinking specifically of northern Rhudaur, Mount Gram, and Carn Dûm), had “murmured against the Men of the West, and rose against them,” that would be right in line with what we do know: Valandur met a violent end, and soon after, some of the people of Arnor “listened … to counsels that came from” Sauron, they “raised a rebellion, and he that is now the Chief of the Nine drove” the Dúnedain first out of Rhudaur, then out of Cardolan, and finally out of Fornost the Norbury, so that “all the Northland has now long been waste; and all that are left of Elendil’s folk are few.” The intention of the nascent story that is presented in this part of The Treason of Isengard is of course to have “Aragorn Tarkil” claim the throne of “Ond,” and it evolves into the story of how Aragorn son of Arathorn claimed the throne of Gondor; but I think that it is also the germ of the story of the decline and fall of Arnor through intrigue, treachery, internecine warfare, and the rebellion of a resentful and disloyal non-Númenórean population. There are, of course, vast differences between the nascent story and the final Tale, but even the names of some of the people and places that are important to the history Arnor have begun to appear. In the case of Valandur, the name remains in unaltered form.

|

|

|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:37:22 GMT

Gordis

Excellent analysis, Alcuin, thank you for sharing.

Of course, most of your points are irrefutable.

But I still do not believe that the WK was in the North as early as TA 600. After all, it is stated in the Appendices that he came to Angmar around 1300.

Also I think that you overestimate the importance of the name Valandur used both in HOME and in App.A - but used for two different persons:

QUOTE

Alcuin: There are, of course, vast differences between the nascent story and the final Tale, but even the names of some of the people and places that are important to the history Arnor have begun to appear. In the case of Valandur, the name remains in unaltered form.

Later on, in the "The Treason of Isengard" there is this draft for the passage of the Argonauth:

QUOTE

'Under their shadow nought has Eldamir son of Eldakar son of Valandil to fear', and my copy retains it. This might be thought to be a mere inconsistency of correction on his part; but this is evidently not the case, since on both manuscripts he added a further step in the genealogy: 'Eldamir son of Valatar son of Eldakar son of Valandil.' Since he did not strike out 'Eldamir son of Eldakar son of Valandil' on my copy, but on the contrary accepted the genealogy and slightly enlarged it, it must be presumed that Eldamir beside Aragorn was intentional; cf. FR (p. 409): 'Under their shadow Elessar, the Elfstone son of Arathorn... has nought to dread!', and cf. Eldamir > Elessar, p. 294. My father's retention of the genealogy, with the addition of Valatar, is also remarkable in that it shows him still accepting the brief span of generations separating Aragorn from Isildur.

To me it seems that Tolkien simply used Vala-something and Elda-something freely when he drafted the names of the kings of the Line of Elendil. Note that here there is no "Valandur", instead, Valandil appears.

And some of these guys: Valandil, or Eldacar, or Valatar, had to be driven out of Minas Tirith, if Tolkien still retained this story.

"Valandur" who was driven out of Minas Tirith most likely was a precursor of Valandil, Isildur’s son, not Valandur, the Eight King of Arnor.

|

|

|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:38:20 GMT

Alcuin

Oh, I don’t disagree, Gordis, and I don’t want to read too much into the passages. On page 122, the commentary resumes:

QUOTE

…In these earliest texts, it is interesting to see that the Sword that was Broken existed before the story that it was broken beneath Elendil as he fell: indeed it is not clear that at first it was indeed Elendil’s sword, not how Valandur (whose sword it was) was related to him (though it seems plain that he was a direct descendant of Elendil: very possibly he was to be Elendil’s son).

In the passage (iii) [this commentary comes at the end of (iii), not (ii) as in the first post, so the story has changed considerably by now – A.] the final story of the Broken Sword is seen at the moment of its emergence. Valandil appears as the son of Isildur…

I agree with you that the best interpretation of what happened is that Valandur > Valandil, both sons of Isildur, or Valandur son of Elendil > Valandil son of Isildur son of Elendil. In the next version, Elendil and Valandil are brothers, the “‘kings of Númenórë’”, and while Elendil, the chief king, settled in the north, Valandil sailed up Anduin.

Text (iii) initially reports Elendil having three sons, Ilmendur the eldest and founder of and “ruler [of] Osgiliath, the name of the city being appropriate to his own name (Ilmen, region of the stars), as were the cities they ruled to his brothers’ names,” i.e., Isildur in Minas Ithil and Anárion in Minas Anor.

Again, I am not trying to overreach in analyzing the texts. But I think that we can read the discarded texts and from them glean some sense of

when and how Tolkien developed the names of the people and places in the story,

some idea of the general themes that underlay the stories, and

a better gist of what is so far unpublished about Arnor, a kingdom whose fragmentation is important to the story and interesting to those of us who are writing here about one of its daughter kingdoms struggling against the cunning and ruthless King of Angmar.

The texts are what they are: the primitive and nascent form of a Tale that would become far richer and more variegated as time went on; but there is precious little about the breakup of Arnor. I am actively seeking more information from the material that has been released. This is one little nugget suggesting that the stream may yet reveal a greater wealth of information.

|

|

|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:41:27 GMT

Olmer

Very interesting observations, Alcuin, which is in some way strengthen up my theory about a total destruction of Arnor due to Gondorean genocide.

QUOTE

I think that it is also the germ of the story of the decline and fall of Arnor through intrigue, treachery, internecine warfare, and the rebellion of a resentful and disloyal non-Númenórean population.

Yes! Thank you! My point just the same. Arnor was slowly turning its back to Gondor, and eventually would become a very inhospitable place and a breeding ground for troubles..

"No one lives in this land. Men once dwelt here, ages ago; but none remain now. They became an evil people, as legend tell, for they fell under the shadow of Angmar. But all were destroyed in the war that brought the North Kingdom to its end." (“FoTR”)

It is under question that ALL of them became evil, as Gordis one time joked, evil women, evil babies and evil chickens, but the fact is that ALL population, including kids, women and elderly folks were whiped off in the war.

There, where walked over the united Army of Gondoreans and Elves, once inhabited by people places became a barren wasteland.

“Then so utterly was Angmar defeated that NOT a MAN nor an orc of that realm remained west of the Mountains” (“Appendix A)

I understand the wrath of the King of Angmar for a total annihilation of his people and his kingdom, and this rage was directed not on Glorfindel or Cirdan, but on the obvious initiator of such bloody extermination, the Chief Commander Earnur."So ended the evil realm of Angmar; and so did Earnur, Captain of Gondor, earn the chief hatred of the Witch-King..”

|

|

|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:42:12 GMT

Witch-king of Angmar

Olmer, it is very good to see you back. Your well thought out observations are always appreciated and studied.

There is such a wealth of material here that I sometimes get impatient to jump about 600 years from 1346 to 1974, Third Age, and show what happened after these early years. Alas, we cannot do that, because we first have to finish this story before we go to anything else. We are hampered with only few participating, and so we do not move very fast.

I hope to see you back again with your much appreciated comments.

|

|

|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:42:45 GMT

Gordis

I am happy to see you here, Olmer!

As far as I understand, Alcuin was putting the blame for the decline of Arnor on the Witch-King, even the division of Arnor which happened as early as TA 861.

You, Olmer, put the blame for the final destruction of Arnor on the Gondorians. And here (as usual) I both agree and disagree.

I think that most of Arnor's remaining population was destroyed by the Angmarians. Fornost seemingly became a mass grave for its citizens and for the refugees from the nearby farms - it was not called Deadmen's Dike for nothing.

As for the Gondorians - undeniably they followed the scorched earth policy when passing through former Rhudaur and Angmar in 1975. Here you are dead right.

“Then so utterly was Angmar defeated that NOT a MAN nor an orc of that realm remained west of the Mountains” (“Appendix A)

Yes, and note that those who dwelt east of the Mountains were soon wiped out or driven away by the Gondorian allies - the people of Rhovanion, ancestors of the Rohirrim.

I agree this cruelty must have been made on Earnur's order because the Witch King was after him ever since. It must have been something out of the ordinary for the nazgul to take it so much to heart. Probably the Witch-King even chose his new abode in Minas Ithil to be closer to his prey. Glorfindel and Cirdan have once defeated Angmar - back in 1409, but there was no question of wiping away its population. It must have been an innovation introduced by the Gondorians.

And there is another aspect of the Gondorian "help" in 1975 - the fate of the remaining farms in Arthedain and Cardolan lying in friendly territory. An enormous Gondorean army (not to mention the Elves) and the fleet stationed in Mithlond needed something to eat. I think the requisitions made for the marching army were the last straw that broke Arnor's economy. The "barbarian" part of the remaining population simply left the blighted land seeking refuge in Dunland and maybe also in places like Dale etc. And the remaining Dunedain of Arnor had no option than to move to the Angle, where at least they could get help from Rivendell to survive winters.

Really difficult to tell what was worse - Angmar invasion or Gondorian help!

|

|

|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:43:17 GMT

AlcuinHm. I think we can get a better picture of what Tolkien imagined by reference to real events. My read on the ruin of Cardolan in the war of III 1409 and the end of Arthedain in III 1974-1975 is that the Dúnedain who were found outside their fortified places were slaughtered by the soldiers of Angmar. That would indicate that genocide, insofar as it was practiced during these wars, was not a Dúnedain practice but one of Angmar: note that at the end of the War of the Ring, Aragorn II showed mercy to the Easterlings and Southrons who were captured. The implication is that one of the spurs used by the Witch-king to drive on his troops was similar to that later used by Saruman to incite the Dunlendings: drive out the interlopers (whether they are truly “invaders” or not) and seize their territory. Real history is replete with examples of such warfare, but the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Roman Britain AD 449-600 (See St Gildas, De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, “Of the Ruin and Conquest of Britain,” written in the mid-sixth century about people and events that Gildas himself witnessed: it is a first-hand account) and the Viking incursions ca. AD 800-1066 (beginning at Lindisfarne and ending with the defeat of Harold Hardrada by Harold Godwinson at Stamford Bridge scarcely 3 weeks before Harold Godwinson and the Anglo-Saxon nobility fell before William the Conqueror at Hastings). Briton resistance to the Anglo-Saxon invasion is the source of one of Europe’s oldest and most famous “chivalric” tales, that of King Arthur. (Arthur is believed to have died around the global catastrophe that brought down many kingdoms after AD 535, including: the Anglo-Saxon conquest of Britannia; the end of Byzantine expansion, and the rise of Islam as a result of the final catastrophic collapse of the (then) 1,500 year-old Marib Dam and the slaughter and conquest of Islam’s neighbors; the rise of the Turks and the beginning of their migrations and invasions to the west; the fall of the Northern Wei dynasty in China (the kingdom depicted in the story Mulan), who recorded that in mid-November and early December AD 535, “Yellow dust rained down like snow” (Li Yan-shou of Tang in Nan Shi, or History of the Southern Dynasties, composed during the period AD 627-649), probably as a result of volcanic activity that was the source of all the trouble; the fall of the Teotihuacan empire among the Mayan kingdoms, leading to the subsequent rise of Calakmul and Caracol; and the end of the Moche and Nazca civilizations in the Andes.) Let’s examine these two disasters – that’s what they were for the invaded peoples who kept written records of which Tolkien was recognized as a professional, academic expert – for some comparisons to the fall of Arnor. In both cases – the invasion of Roman Britannia and the Viking incursions – the inhabitants were forced to take refuge in fortified places to avoid murder, rape, and captivity into slavery. (I am looking for an historical example of people, probably Britons, taking refuge in the barrows and cairns of their ancestors to escape the invaders, a predecessor story to the Dúnedain of Cardolan taking refuge in the barrow-downs.) The obvious problem in these cases, as at Lindisfarne in AD 793, was that strongholds might be overrun, and all their inhabitants and refugees put to the sword. (Hence the prayer of Alcuin of York, chief councilor of Charlemagne: “From the fury of the Northmen, O Lord deliver us.”) This is true in many places: consider also the classic American settlers’ story, in which Indians drive the settlers into a fort or strong house, who are slaughtered if their defense fails. (The story in reverse.) This is what I think Tolkien envisioned happening to the Dúnedain in Arnor: they were attacked by savages, they fled into their fortifications to avoid slaughter, but eventually these fortifications were reduced and the inhabitants put to the sword. The last to be overrun was Fornost Erain, and with its fall followed the slaughter of the greater part of the remaining Dúnedain inhabitants of Arnor. As a philologist, Tolkien was probably familiar with a linguistic curiosity connected with the Viking conquest of Orkney and Shetland: 90% of the placenames in those islands have Norse roots, although the islands have been inhabited since the Ice Age. (Indeed, the ancient inhabitants were quite sophisticated, even building stone dressers and cabinets in their sturdy habitations thousands of years ago.) This remarkable fact has long been noted by philologists: the implication is that none of original inhabitants were spared, none of the local women taken to wife by the invaders to teach their children the old names of places after Vikings took possession of the islands. There is a sharp line archeologically between the Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain and the Britons who lived there, between the invaders and the invaded. The animosity ran so deep that when in AD 601 Pope Gregory the Great made the missionary St Augustine of Canterbury Archbishop of Britain, the Britons, who had been faithful Christians for 550 years, refused to recognize the authority of Augustine. When the Danish invasion of Anglo-Saxon England was halted by Alfred the Great in AD 878, he forced Guthrum, leader of the Danes, to establish a boundary line between the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes; it was not until almost a quarter-century later that Edward the Elder was able to incorporate the Danelaw into England: towns and ancient fields in the old Danelaw are laid out differently from those in the Anglo-Saxon west. (We also get jury trials from the Danelaw.) Archeologically, there is a distinct difference between Danish settlements in East Anglia and Saxon settlements in Mercia or Wessex. (Tolkien identified himself as a descendent of the Mercians: e.g. Letter 95; Farmer Giles of Ham may loosely based on Mercia, or even on the Roman Briton kingdom that preceded it.) So we can explain the near-annihilation of the Dúnedain in the North. What of the destruction of the folk of Angmar? For that, I think, we again can look to real history, and to what is implied but left unsaid in Tolkien’s story. The Witch-king of Angmar waged war upon the daughter-kingdoms of Arnor to bring an end to the Dúnedain of the North and to capture one or more of the palantíri they controlled. The people of Angmar waged war – why? Do Broggha and the Jarl seek to become one with the Dúnedain? No! They seek to supplant them! We know from “Appendix A” of Return of the King how this must inevitably conclude: in 1409, “Rhudaur was occupied by evil Men subject to Angmar, and the Dúnedain that remained there were slain or fled west” into Arthedain and Cardolan. The people of Angmar, like the Dunlendings, seek better lands, better fields in which to grow food and graze herds, warmer climes, and the wealth of the Dúnedain that may be taken as spoils. When the Great Army of the Danes drove the Angles from Northumbria and East Anglia, they brought their own families to settle the land. When the Saxons took control of Kent and Sussex and Wessex, they brought their families with them. (I think Hengest and Horsa were Jutes, for the invaders were the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes, who came first, probably as laeti, mercenaries who under Roman law agreed to settle on agricultural land and accept military responsibilities, but cheated of their payment by Vortigern, leader of the Britons. (Vortigern might have been a title among the Britons rather than a proper or personal name: the issue arose several years ago among scholars and has become a matter of contention.) If Hengest were a Jute, that would explain how he would know the family of Beowulf, a Gaet: Jutland and Gotland are quite near one another.) In like manner, I believe that the people of Angmar took control of lands that had belonged to ancient Arnor, quickly bringing their families to live there. Because we know that Arvedui fled into the wild from the fall of Fornost during the winter, we know when the city fell: in late fall or early winter. We know that the attack was sudden and unexpected; I believe that implies that the folk of Angmar put everything they had into the war, hoping to seize the foodstuffs and siege-stores of the Dúnedain to sustain themselves through the winter months. (It is likely that Arvedui and his predecessors kept as much as three years of grain in storage against invasion and siege; they certainly maintained as much as possible!) Since the Witch-king set himself up in Fornost after conquering it, we know that the city remained habitable, which means that it was not burned to the ground or in ruins: probably the gates were destroyed by means similar to those employed against the Great Gate of Minas Tirith a millennium later: had Minas Tirith fallen in III 3019, it would have remained habitable to the army of Morgul. (Has anyone else noticed the consonation and alliteration of the words “Morgul” and “Mongol”?) I think the folk of Carn-Dûm were then moved to their new capital, Fornost, probably given some new name by its conquerors. How then came the people of Angmar to ruin? I believe that is made clear enough in “Appendix A”: the “...Witch-king of Angmar ... was … dwelling … in Fornost, which he had filled with evil folk, usurping the house and rule of the kings. In his pride he did not await the onset of his enemies in his stronghold, but went out to meet them [the combined armies of Lindon, the Dúnedain survivors of Arthedain, the expeditionary force of Gondor, and Rivendell from the east], thinking to sweep them, as others before, into the Lune.” He committed all his forces to battle again, but this time, he was defeated, his army annihilated in the field. It is likely that at this point Fornost was burned and all its treasures and stores (what was left of them) destroyed, and many of the people of Angmar who were in it died in the fire. The women and children of the folk of Angmar who survived might have been spared, but they could not expect to be allowed to remain in what had been the territory of Arthedain: most would starve on their way back to the far north; the others would cross the mountains into eastern Angmar in the northern Vales of Anduin, where the ancestors of the Rohirrim living there defeated them. (“Appendix A”, “II The House of Eorl”: “…when … they heard of the overthrow of the Witch-king, they … drove away the remnants of the people of Angmar on the east side of the [Misty] Mountains.”) It does not appear that Carn-Dûm was completely abandoned before the combined forces of the Elves and Dúnedain reached it in III 1975: the Witch-king was making for his old stronghold when he was overtaken by the cavalries of Gondor and Rivendell. However, its male inhabitants were committed to the army, and all of them were dead, killed in the aforementioned battle when the Witch-king “went out to meet” his enemies before they arrived at Fornost; I assert that many of its people had probably moved south to Fornost after Angmar took control of that city; and so those who remained in Carn-Dûm, which had been deliberately depopulated, were unable to fend off the follow-up assault by the Dúnedain and Elves. The city was probably burned to the ground, and its survivors fled eastwards over the Mountains, where, if they survived the passage in the winter and dearth of early spring, they then faced the Men of Rhovanion in the Vales of Anduin. Thus the end of the People of Angmar. I don’t think it is either reasonable or textually defensible to believe that the Dúnedain or the Elves put the women and children of the Men of Angmar to the sword, as the army of the Witch-king had done to the Dúnedain; but they must surely have routed and driven them out of the old territories of Arthedain, Rhudaur, and Cardolan, with the inevitable result that most of those folk died in their trek back to their ruined towns and farms in the far north, if indeed they knew the way or had any place there to go. And despite the political correctness and silly notions of late twentieth and early twenty-first century Americans and Europeans, there is no reason in human history to imagine that the surviving Dúnedain of the North, their kinsmen from Gondor, or the Elves of either Lindon or Rivendell would do anything else: had they allowed these invaders to remain, they would be ensuring the deaths of whatever Dúnedain of the North survived the slaughter of the war. -|- There is no indication that the expeditionary force of Gondor foraged for food in Arnor or Eriador, but quite the contrary: from “Appendix A”, QUOTE …when Eärnur came to the Grey Havens … So great in draught and so many were his ships that they could scarcely find harborage, though both the Harlond and the Forlond also were filled; and from them descended an army of power, with munition and provision for a war of great kings. But I must agree with Gordis that “the Gondorians … followed scorched earth policy when passing through former Rhudaur and Angmar in [III] 1975.” And not only the expeditionary force of Gondor, but also the survivors of the Dúnedain of the North, and the Elves of Lindon and of Rivendell: while they might not put the inhabitants to the sword, they burned out their farms, villages, and towns in order to drive them off. Death by starvation and illness would be unavoidable for most of the surviving folk of Angmar, even as it had been for the Dúnedain of the North.

|

|

|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:43:55 GMT

Valandil

Alcuin - Great post - very interesting, exhaustive and helpful.

There was one item I didn't catch completely from the historical examples... why exactly did the Britons not accept Augustine of Canterbury in AD 601?

And... one small note about your account of the fall of Angmar. Whatever survivors of western Angmar who made it into the eastern parts didn't find the ancestors of the Rohirrim waiting for them. The Eotheod moved north (under Frumgar) into those parts in 1977, according to LOTR Appendix B - so it was about 2 years after the defeat of Angmar's army.

I've even wondered if Gandalf or some other influential figure suggested this move to the Eotheod. After the fall of the last of Arnor's daughter kingdoms, and the subsequent fall of Angmar - there was almost a vacuum in the far northern parts of Middle Earth. There was Thranduil's realm in Mirkwood, of course... but even the Dwarves were still in Moria (for just a few more years). Scatha may have been a known threat - since it was Fram, son of Frumgar, who slew him. Otherwise - there was a real lack of power in the north until the Eotheod arrived.

I wonder too - if Scatha was in league with the Witch-King while Angmar was around.

|

|

|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:44:49 GMT

Alcuin

QUOTE (Valandil @ Dec 17 2006, 09:18 AM)

There was one item I didn't catch completely from the historical examples... why exactly did the Britons not accept Augustine of Canterbury in AD 601?

The Britons (whom the Anglo-Saxons called Wylisc (West Saxon) or Wælisc (Anglian); the Online Etymology Dictionary quotes Tolkien as defining Welsh as “common Gmc. [Germanic] name for a man of what we should call Celtic speech,” but also applied to speakers of Latin; note also that Tolkien was extremely fond of Welsh) considered the Anglo-Saxons to be invaders and interlopers, unwelcome destroyers of their lives and property.

By establishing the Archbishopric of Canterbury with Augustine as its first Archbishop, making that see the primary see of the island, Pope Gregory was effectively acknowledging the ascendancy of the Anglo-Saxons, and making the Britons subject to them. There were some discussions and meetings between the Britons and the authorities at Canterbury, but all to no avail: there could be no reasonable resolution expected in this instance, unless perhaps the Pope had appointed one of the Britons to be Archbishop, which he was unlikely to do in order to avoid provoking the Anglo-Saxons. The Welsh remained Christians (though they are no longer Catholic, having converted en masse to Protestantism during the years of the Reformation as part of the Church of England; the Church in Wales separated from the Church of England in 1920), and the Anglo-Saxons became Christians, so the Church in Rome obtained a better situation despite the difficulties. A similar situation arose in Ireland, where the Church had been established by St. Patrick.

The online Catholic Encylopedia (1919 edition) offers this explanation:

QUOTE

Undoubtedly the most certain facts in Welsh history at this period are those … connecting St. Augustine with the Welsh bishops. Pope Gregory the Great twice committed the British Church to the care and authority of St. Augustine and the latter accordingly invited them to a conference upon the matters in which they departed from the approved Roman custom. They asked for a postponement, but at a second conference the seven British bishops present altogether refused to accept Augustine as their archbishop or to conform in the matter of the disputed practices. The points mentioned by Bede prove that the divergences could not have been at all fundamental. No matter of dogma seems to have been involved, but the Britons were accused of using an erroneous cycle for determining Easter, of defective baptism (which may mean, it has been suggested, the omission of confirmation after baptism), and thirdly of refusing to join with Augustine in any common action for the conversion of the Angles. ... It may have been partly as a result of this uncompromising hatred of the Saxons and the Church identified with them, that we read during all this period of a more or less continual emigration of the Britons to Armorica, the modern Brittany.

The “disputed practices” in question were those of the Celtic Christians, including the tonsure (the way monks cut their hair) and some matters of rites, but the elided portion toward the end says that “all these were matters of discipline only,” so any disputes arising from them could be resolved if both parties had been willing – they were not.

QUOTE (Valandil @ Dec 17 2006, 09:18 AM)

And... one small note about your account of the fall of Angmar. Whatever survivors of western Angmar who made it into the eastern parts didn't find the ancestors of the Rohirrim waiting for them. The Eotheod moved north (under Frumgar) into those parts in 1977, according to LOTR Appendix B - so it was about 2 years after the defeat of Angmar's army.

I've even wondered if Gandalf or some other influential figure suggested this move to the Eotheod. ... Scatha may have been a known threat - since it was Fram, son of Frumgar, who slew him...

I wonder too - if Scatha was in league with the Witch-King while Angmar was around.

You are correct about the origins of the Éothéod. I had given no thought to the influence of Gandalf or Radagast, who had close relations with the Men of the Vales of Anduin, but I agree that is a possibility. I don’t know any more about Scatha and his origins (except that he like Smaug came from the Withered Heath, probably not pertinent to this discussion), but if he had been in league with Angmar, surely the Witch-king would have used the dragon against Arthedain and possibly against Rivendell, as Sauron planned to use Smaug against Rivendell a thousand years later.

|

|

|

|

Post by Witch-king of Angmar on Dec 26, 2006 21:45:50 GMT

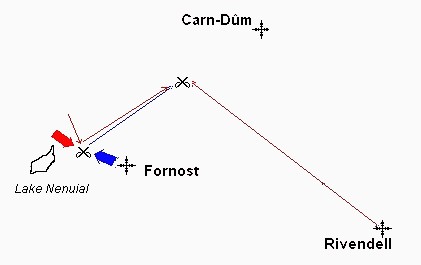

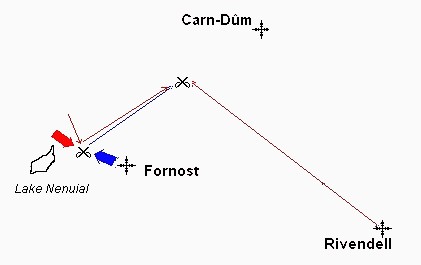

This is how I interpret the material concerning the end of the kingdom of Angmar in Return of the King, “Appendix A”. I prepared a sketch to more easily describe the situation I think Tolkien has laid out for us.  - Círdan, leading the combined forces of Lindon, the surviving Dúnedain of the North, and most of the expeditionary force of Gondor, approaches Fornost from the Hills of Evendim. (Big red arrow)

- The Witch-king, whose army has occupied Fornost, leads his forces out to confront them between Lake Nenuial and the North Downs. (Big blue arrow)

- The two armies engage. As Angmar’s lines begin to waver, Eärnur leading the cavalry of Gondor charges into the battle from the north. (Thin red line headed south).

- Angmar is defeated. The Witch-king leads a retreat in haste towards Carn-Dûm, with Eärnur and the cavalry of Gondor in hot pursuit. (Thin blue and red lines headed towards Carn-Dûm.)

Before the Witch-king and his remaining forces can reach their city, a force from Rivendell led by Glorfindel cuts off their retreat. (Thin red line from Rivendell) What is left of the army of Angmar is utterly destroyed. The Witch-king alone escapes into the night.

|

|